Germany–Switzerland relations

| |

Germany |

Switzerland |

|---|---|

Diplomatic relations between Germany and Switzerland are Switzerland's closest. There are over 200 agreements between Switzerland and Germany; and between Switzerland and the European Union (EU), of which Germany is a member.[1] Switzerland is also part of the EU's Schengen Area which abolishes international borders between Schengen states.

The two share a border and a language (German is one of Switzerland's four official languages). More than 44,000 Germans commute across the border every day and there is strong cross border cooperation, particularly on the Upper Rhine and Lake Constance. However relations are strained by unresolved tax issues and German restrictions on flights into Zürich.[1]

History[edit]

Holy Roman Empire and Old Confederacy[edit]

From around the year 1000, the territories of present-day Switzerland were part of the Holy Roman Empire, which extended over large parts of Western and Central Europe. However, it never constituted a state in the modern sense, but was a loose alliance of individual states and territories. In the High Middle Ages, the land west of the rivers Aare and Reuss belonged to Burgundy and the land east of it to the Duchy of Swabia. As the mountainous Alpine region was far removed from any imperial authority, various territories organized themselves into alliances in the 13th and 14th centuries (Old Confederacy), which were able to emancipate themselves from the authority of the Habsburgs over time. The Confederacy saw themselves as part of the Empire and took part in the Imperial Diet. However, when a Habsburg was on the throne, they distanced themselves from the emperor and drew closer to the other imperial estates. The Luxembourg Emperor Sigismund transferred the Aargau from the Habsburgs to the Confederacy in 1415 and gave the Eight Old Cantons imperial immediacy.[2]

In the 15th century, the Old Swiss Confederacy alliance was increasingly seen as a unit and an independent identity was formed. In 1521, the Confederacy concluded an alliance with the Kingdom of France, which made the French the protector of the Confederacy against the Habsburgs and increasingly influenced Switzerland more strongly than the Empire. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Confederacy no longer participated in the institutions of the Empire and during the Thirty Years' War, the Confederacy remained neutral while the Empire was devastated. With the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the Swiss finally broke away from the Holy Roman Empire and the formal supremacy of the Holy Roman Emperor and thus became sovereign. However, some areas of Switzerland, such as the Prince-Bishopric of Basel, remained part of the Empire until the 1803 Reichsdeputationshauptschluss.[2]

German Confederation and Switzerland[edit]

Conflict arose between the monarchist German Confederation and liberal Switzerland over Swiss asylum policy when Switzerland became a refuge for German revolutionaries and liberals after the Carlsbad Decrees. After the Carlsbad Decrees (1819), Metternich put Switzerland under pressure, forcing it to pass an Convention in 1923, which included surveillance of the domestic press and restrictions on the right of asylum. Austria had previously threatened to invade. During the Baden Revolution of 1848/49, there was renewed conflict when Baden revolutionaries used Switzerland as a base, which is why the German Customs Union abolished the customs privileges granted in the 1830s in 1851. A conflict between Prussia and Switzerland was settled peacefully in 1857 after the Neuchâtel Crisis.[3]

German Empire and Switzerland[edit]

After the unification of Germany, Switzerland tried to maintain good relations with the new great power that had emerged on its borders. Under Otto von Bismarck, there were again disputes over Swiss asylum policy, this time over the admission of socialists after the Sozialistengesetz. Under Wilhelm II, relations were problem-free and a state visit by Wilhelm in 1912 triggered an enthusiastic reaction in German-speaking Switzerland and mixed reactions in French-speaking Switzerland. After trade relations intensified, the Empire became Switzerland's most important trading partner and by 1910 there were already 220,000 Germans living in Switzerland. The First World War divided Switzerland internally, as German-speaking Switzerland sympathized with Germany and French-speaking Switzerland with France, which was further fuelled by foreign war propaganda. As part of its policy of neutrality, however, Switzerland remained neutral in foreign policy, which was a difficult balancing act as Switzerland only bordered on warring parties.[4]

Nazi Germany and Switzerland[edit]

The rise of Adolf Hitler caused great concern in Switzerland and was only welcomed by the right-wing front movement (Frontbewegung). Hitler's promise to respect Swiss neutrality was given little credibility by the swiss. At the same time, economic relations with Germany were of great importance to the Swiss. In 1935, the Jewish German journalist Bertold Jacob-Salomon was kidnapped by the Nazi regime on Swiss soil, but was released after protests by the Swiss government, which was a remarkable success for Swiss foreign policy. A year later, the Gustloff affair led to furious propaganda by the Nazi press against Switzerland and the banning of the NSDAP foreign organization in Switzerland.[4]

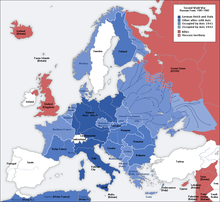

After the start of the Second World War, Switzerland maintained its policy of neutrality. When the country was temporarily completely surrounded by the Axis powers due to the German occupation of France, Switzerland's room for maneuver was severely limited. However, Switzerland announced its readiness to resist an attack on it and the Axis had other priorities during the world war, even if the National Socialists regarded Switzerland as part of a Greater Germanic Reich. Switzerland pursued a restrictive policy towards refugees from Nazi Germany and turned away numerous persecuted persons. After Hitler's defeat became apparent in 1943, Switzerland's admission policy finally became more liberal.[4]

During the years 1940 to 1945, the German Reichsbank exchanged 1.3 billion Swiss francs worth of gold (equivalent to approximately 18 billion francs adjusted for inflation to 2019) with Swiss banks. This transaction facilitated the acquisition of Swiss francs and other foreign currencies, which were subsequently utilized to procure strategically vital raw materials such as tungsten and oil from neutral nations.[5]

Cold war[edit]

On July 24, 1945, the Swiss Federal Council implemented the decision it had been preparing since May 1 and had taken on May 8: Switzerland ended its recognition of the German government. The state continued to exist for Switzerland, but was unable to act due to the lack of a government.

Due to anti-democratic activities, many Germans were expelled from the country and National Socialist organizations were banned. After the closure of all representations, Switzerland, under the leadership of Hans Zurlinden and later the former Berlin ambassador Frölicher, took over the German Representation of Interests (DIV) in Switzerland on a fiduciary basis, a kind of management for a future legitimate German state. The whole thing took place under the suspicious eyes of the Allies, who wanted to confiscate private German assets and take over the German files now under the jurisdiction of the Swiss Foreign Ministry. While the files “managed” somewhat by the Swiss were later handed over, the Allies relented on the private assets in the course of the emerging Cold War.

In 1951, West Germany recognized the debts from the Nazi era and Switzerland released the blocked German state assets. German authorities gradually took over the tasks of the DIV so that it could be dissolved in 1953. A German embassy was opened again. In the early post-war period, the modern friendly neighborly relations were established.

In addition to relations with the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), Switzerland also maintained relations with the German Democratic Republic (GDR) between 1972 and 1990. While the FRG was a member of NATO during the Cold War, the GDR was a member of the Warsaw Pact. Switzerland maintained its policy of neutrality.

After 1990[edit]

A dispute over fiscal matters and tax policy issues was settled with the Germany-Switzerland tax agreement in 2011.

Economic relations[edit]

Germany is Switzerland's most important trading partner: a third of all imports to Switzerland come from Germany (more than Switzerland's next four trading partners combined). Switzerland is also the third largest foreign investor in Germany (after other EU states and the United States) and Swiss companies also employ 260,000 people in Germany. Germany is the fifth largest investor in Switzerland and German companies employ 94,000 people in Switzerland.[1]

The two are also each other's largest group of foreign visitors, and Switzerland is the most popular emigration destination for Germans. The German population in Switzerland is the second largest foreign group (after Italians) and the number of Swiss living in Germany has increased by 11% to 76,000. Many of these emigrants are highly qualified professionals such as university teachers.[1]

Diplomatic missions[edit]

- Germany has an embassy in Bern.

- Switzerland has an embassy in Berlin and consulates-general in Frankfurt, Munich and Stuttgart.

-

Embassy of Switzerland in Berlin

-

Consulate-General of Switzerland in Munich

-

Consulate-General of Switzerland in Stuttgart

See also[edit]

- Foreign relations of Germany

- Foreign relations of Switzerland

- Büsingen am Hochrhein

- German immigration to Switzerland

- Germany–Switzerland border

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Bilateral relations between Switzerland and Germany, Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs

- ^ a b "Heiliges Römisches Reich". Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ "Deutscher Bund". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ a b c "Deutschland". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. Retrieved 2024-05-15.

- ^ Bergier, Jean-Francois; W. Bartoszewski; S. Friedländer; H. James; H. Junz; G. Kreis; S. Milton; J. Picard; J. Tanner; D. Thürer; J. Voyame (2002). Final Report of the Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War (PDF). Zürich: Pendo Verlag GmbH. p. 107. ISBN 3-85842-603-2.