Portal:Stars

IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime as a fusor, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: NASA/ESA/HST

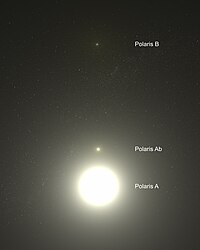

Polaris (α UMi / α Ursae Minoris / Alpha Ursae Minoris, commonly North(ern) Star or Pole Star, or Dhruva Tara and sometimes Lodestar) is the brightest star in the constellation Ursa Minor. It is very close to the north celestial pole (42′ away as of 2006[update], making it the current northern pole star. Polaris is about 430 light-years from Earth and is a multiple star. α UMi A is a six solar massWieland page 3: masses of A and P ... (6.0+1.54M⊙) F7 bright giant (II) or supergiant (Ib). The two smaller companions are: α UMi B, a 1.5 solar mass F3V main sequence star orbiting at a distance of 2400 AU, and α UMi Ab, a very close dwarf with an 18.5 AU radius orbit. There are also two distant components α UMi C and α UMi D. Recent observations show that Polaris may be part of a loose open cluster of type A and F stars. Polaris B can be seen even with a modest telescope and was first noticed by William Herschel in 1780. In 1929, it was discovered by examining the spectrum of Polaris A that it had another very close dwarf companion (variously α UMi P, α UMi a or α UMi Ab), which had been theorized in earlier observations (Moore, J.H and Kholodovsky, E. A.). In January 2006, NASA released images from the Hubble telescope, directly showing all three members of the Polaris ternary system. The nearer dwarf star is in an orbit of only 18.5 AU (2.8 billion km; about the distance from our Sun to Uranus) from Polaris A, explaining why its light is swamped by its close and much brighter companion. Polaris is a classic Population I Cepheid variable (although, it was once thought to be Population II due to its high galactic latitude). Selected article - Photo credit: user:Anynobody

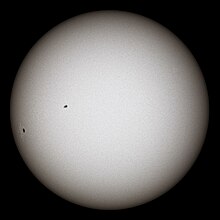

The solar mass () is a standard unit of mass in astronomy, used to indicate the masses of other stars, as well as clusters, nebulae and galaxies. It is equal to the mass of the Sun, about two nonillion kilograms. This is about 332,950 times the mass of the Earth or 1,048 times the mass of Jupiter. Because the Earth follows an elliptical orbit around the Sun, the solar mass can be computed from the equation for the orbital period of a small body orbiting a central mass. Based upon the length of the year, the distance from the Earth to the Sun (an astronomical unit or AU), and the gravitational constant (G). The value of the gravitational constant was derived from 1798 measurements by Henry Cavendish using a torsion balance. The value obtained differed only by about 1% from the modern value.The diurnal parallax of the Sun was accurately measured during the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769, yielding a value of 9″ (compared to the present 1976 value of 8.794148″). When the value of the diurnal parallax is known, the distance to the Sun can be determined from the geometry of the Earth. The first person to estimate the mass of the Sun was Isaac Newton. In his work Principia, he estimated that the ratio of the mass of the Earth to the Sun was about 1/28,700. Later he determined that this value was based upon a faulty value for the solar parallax, which was used to estimate the distance to the Sun (1 AU). He revised his result to obtain a ratio of 1/169,282 in the third edition of the Principia. The current value for the solar parallax is smaller still, giving a mass ratio of 1/332,946. As a unit of measurement, the solar mass came into use before the AU and the gravitational constant were precisely measured. This is because the determination of the relative mass of another planet in the Solar System or of a binary star in units of solar masses does not depend on these poorly known constants. So it was useful to express these masses in units of solar masses (see Gaussian gravitational constant). The mass of the Sun changes slowly, compared to the lifetime of the Sun. Mass is lost due to two main processes in nearly equal amounts. First, in the Sun's core hydrogen is converted into helium by nuclear fusion, in particular the pp chain. Thereby mass is converted to energy in correspondence to the mass–energy equivalence. This energy is eventually radiated away by the Sun. The second process is the solar wind, which is the ejection of mainly protons and electrons to outer space. The actual net mass of the Sun since it reached the main sequence remains uncertain. The early Sun had much higher mass loss rates than at present, so, realistically, it may have lost anywhere from 1–7% of its total mass over the course of its main sequence lifetime. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA

The Pinwheel Galaxy (also known as Messier 101 or NGC 5457) is a face-on spiral galaxy about 27 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major, discovered by Pierre Méchain. On February 28, 2006, NASA and the ESA released a very detailed image of Pinwheel Galaxy, which was the largest and most detailed image of a galaxy by Hubble Space Telescope at the time. The image was composed from 51 individual exposures, plus some extra ground-based photos. M101 is a relatively large galaxy compared to the Milky Way. With a diameter of 170,000 light-years it is nearly twice the size of the Milky Way. It has a disk mass on the order of 100 billion solar masses, along with a small bulge of about 3 billion solar masses. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Selected biography - Photo credit: Eduard Ender

Tycho Brahe, born Tyge Ottesen Brahe (de Knudstrup) (14 December 1546 – 24 October 1601), was a Danish nobleman known for his accurate and comprehensive astronomical and planetary observations. Coming from Scania, then part of Denmark, now part of modern-day Sweden, Tycho was well known in his lifetime as an astronomer and alchemist. His Danish name "Tyge Ottesen Brahe" is pronounced in Modern Standard Danish as [ˈtsʰyːə ˈʌtəsn̩ ˈpʁɑːə]. He adopted the Latinized name "Tycho Brahe" (usually /ˈtaɪkoʊ ˈbrɑː/ or /ˈbrɑːhiː/ in English) from Tycho (sometimes written Tÿcho) at around age fifteen, and he is now generally referred to as "Tycho", as was common in Scandinavia in his time, rather than by his surname "Brahe". (The incorrect form of his name, Tycho de Brahe, appeared only much later. Tycho Brahe was granted an estate on the island of Hven and the funding to build the Uraniborg, an early research institute, where he built large astronomical instruments and took many careful measurements. After disagreements with the new king in 1597, he was invited by the Bohemian king and Holy Roman emperor Rudolph II to Prague, where he became the official imperial astronomer. He built the new observatory at Benátky nad Jizerou. Here, from 1600 until his death in 1601, he was assisted by Johannes Kepler. Kepler later used Tycho's astronomical information to develop his own theories of astronomy.

TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |